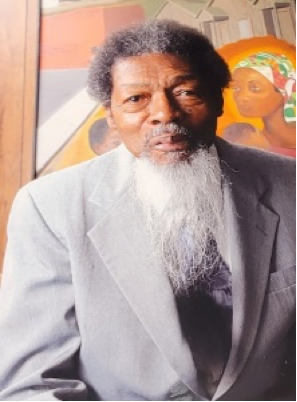

The People’s Lawyer

BY SHAUNDALE RENA

Excerpt from

The People’s Lawyer

As told to me by Bobby H. Caldwell

Bobby H. Caldwell, the “People’s Lawyer,” Connected the Culture, the Community and the Legalization of Cannabis More than 50 Years Ago

The following excerpt is written in his own words, as he described the events to me:

Lee Otis Johnson grew up in Houston. In his younger years, he had been convicted of theft and spent time in the penitentiary. When he came out of prison, he was a firm believer in the principles of Stokely Carmichael and became a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), where he loved a public audience. The more people Lee Otis had around him, the better he could expound his principles and beliefs on what was good for the white man and how wrong the white man was.

I remember the march to Houston’s City Hall after the death of Dr. King when Lee Otis marched and then spoke on the steps of the building. He called the death “the action of racists” and reminded Houston that Black activists should be careful because the police chief and the city mayor were out to get them.

After this riot, in less than three weeks, Lee Otis was arrested and charged with giving a marijuana cigarette to Billy Williams, a police officer who had been sent to the police academy and groomed for the purpose of infiltrating the movement. Billy came out of the academy with a big afro (about six months of growth) and a beard. Lee Otis told me he believed this guy was a police officer when they met and that he had to be very careful with him. So, we knew these charges were something the city of Houston had illegally done.

Attorney Will Gray of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had agreed to take Lee Otis’ case when he was arrested. I think Will did a damn good job of representing him. He filed a motion to transfer venue because the people in Houston were against Lee Otis. Then the Friday before he was to go on trial, I met with Lee Otis at Wheeler Avenue Baptist Church where we were visiting with the founding pastor, Rev. Bill Lawson. I told Lee Otis I was leaving on Monday to go to a Black Power conference. He said, “I wish I could go, but my trial starts Monday.” I told him I knew if he could, he would be there.

That Monday a group of several Black activists and I left Houston by car on our way to Philadelphia for the conference. Wednesday morning, the first thing announced at the meeting was that Lee Otis Johnson had been convicted and sentenced to 30 years in prison for giving one marijuana joint to an undercover police officer, Billy Williams.

When I got back to Houston the following Monday, there were several telephone calls telling me that a committee had been established to free Lee Otis. I met with this committee, and it was recommended that I represent him on appeal. I accepted, and the committee agreed that if Lee Otis was left in prison with only family as visitors, prison officers might do anything to him. It was decided then that I must visit Lee Otis at least once every week.

During that first week after he was jailed, Abbie Luschei (the chair of the committee) spoke with Lee Otis each morning. She found out I needed to be there by eight o’clock for visits. At that time, Cathy and I were acquaintances. She was the liaison and secretary of the committee and volunteered to take me to visit Lee Otis weekly.

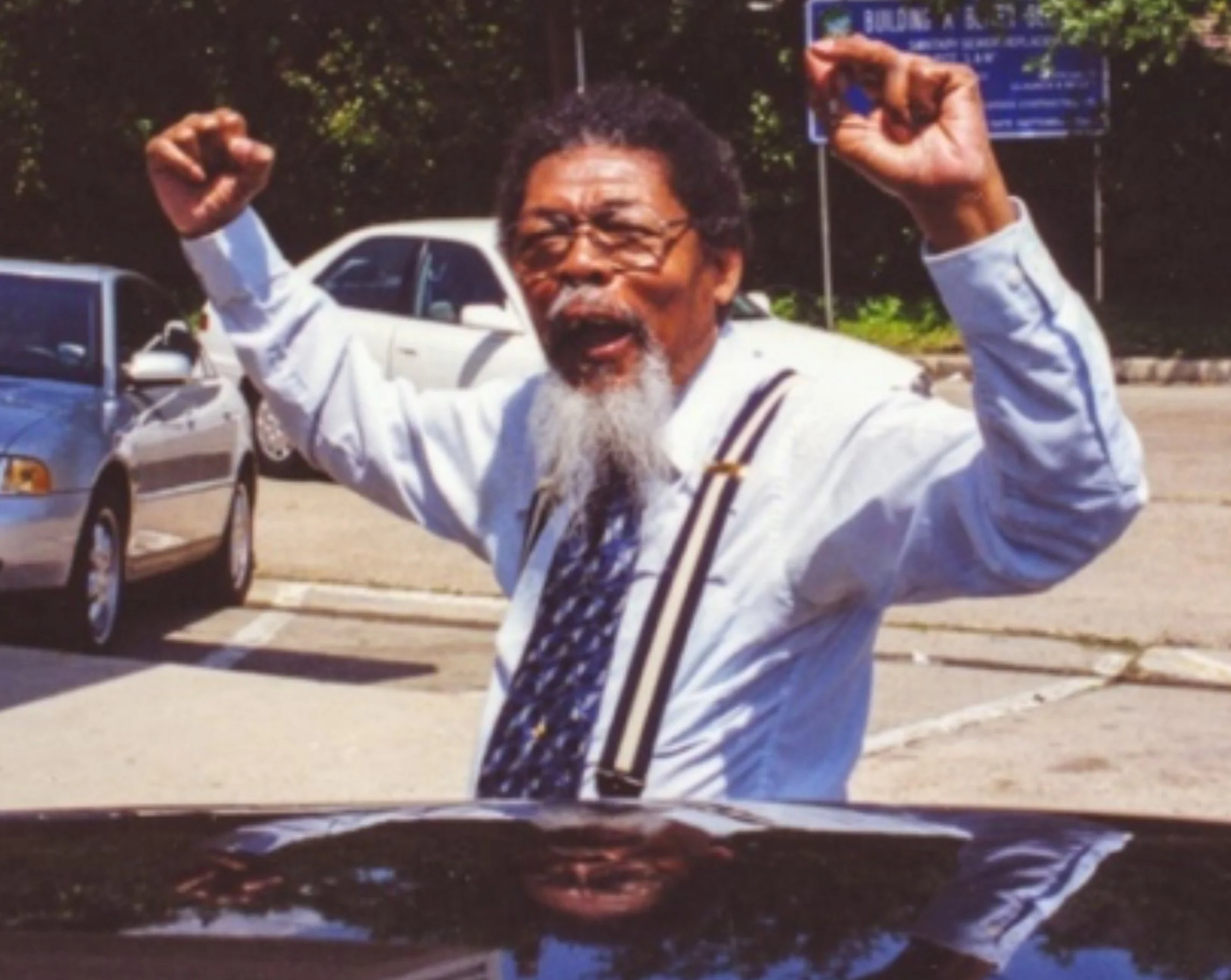

I did not have time to shave in the mornings whenever I had to visit Lee Otis because Cathy showed up at seven o’clock. After a couple of weeks of not shaving, I decided not to cut my goatee until Lee Otis was released from prison. For years it grew, and when the case was won in the court of appeals—and he was finally freed—I decided I looked too good to cut it off and wore my goatee until a few years ago.

We had two hearings before the Court of Appeals. The committee found out that students at TSU were concerned about Lee Otis, and we chartered a bus for them. It was packed. We had a busload of students, and committee members drove their cars, going to the Court of Appeals. The students went in and sat on the floor and tables. The same thing happened when we went down after filing our motion for the court to reconsider their original ruling.

We had organized and started the appeals process to the Criminal Court of Appeals. The conviction was affirmed. We then filed in the Federal Southern District Court and was denied a fair trial. The Circuit of Appeals later affirmed that Lee Otis hadn’t received a fair trial, and we asked for a rehearing on that decision. It was denied. Then we filed a writ of habeas corpus in the US District Court. After the court granted the writ, we set a bond, and Lee Otis was out. The grant of the writ was affirmed by the 5th Circuit of Appeals in New Orleans. Afterwards, the state did not seek to retry.

We had a petition to free Lee Otis. People were going everywhere from decriminalizing the possession of marijuana to lowering the punishment for it. It was during this time that the move started in the country to change marijuana laws after Lee Otis’ case made national headlines. Two years after he had been convicted, the Texas Legislature changed the law regarding possession of marijuana.

Today, because of overturning Lee Otis’ 30-year sentence, the US has legalized a small amount of marijuana, and in some states it has legalized the use of medical marijuana. Mostly all states have decreased the penalties for possession of marijuana cigarettes.

To this extent, in the state of Texas, for possession of two ounces of marijuana or less, the maximum penalty is 100 days in jail and a $2000 fine. For possessing any amount of marijuana, you will not get a life sentence. In fact, President Biden recently granted a pardon to free all federal prisoners who were the victim of possession of marijuana. This has changed significantly, and I’d like to say I had a hand in it.

While we were trying to get Lee Otis out of jail, one of the district attorney’s top assistants spoke to a group of law students at U of H. He also taught part-time at TSU. This assistant stated that District Attorney Carol Vance had told him, “If I would’ve asked for life in the pen for that nigger, they would have given to him,” and laughed. Some of the from U of H called me. I tried to get him fired from TSU and was told that he was wrong for what he had said, but nothing was done about it.

I believe Lee Otis’ case revolutionized the marijuana industry, and the idea of it (even if not the stigma associated with it) changed mainstream America. For possession of marijuana—in the 60s, 70s, and up until recently—if you were Black, you could spend life in the penitentiary. Back then, it seemed everybody had started smoking pot around campuses. In fact, we had one rule when we went to a meeting or a rally: no pot allowed. We knew the police would use it to stop you, and if they found anything on you, that was not good. It was better to not give a reason, or even a probable one. We didn’t even want the police tempted with the possibility.

Photo Credit: Marilyn Bishkin

The People’s Lawyer: A Radical Representation of Change, Courage, and Commitment to Civil Rights, Bobby H. Caldwell, Esq. For more information, visit www.BobbyHCaldwell.com.